Backstory - Jemaa el Fna after the bomb

About 10 years earlier I had been in Marrakech’s main square when a small fight had broken out between a few Moroccan men. They seemed to be arguing over a petty trade, and then somebody threw a punch. There were scuffles and a few blows but nothing more serious than that. Yet within seconds a big van had raced into the square. A dozen men -- some in plain clothes, some in uniform -- swiftly appeared out of the crowd and bundled the perpetrators into the back of the van. In less than a minute there was no trace of the action and I wondered if I might have dreamt it all.

With that in mind I decided -- in advance of my trip -- to try to obtain a filming permit from the Ministry of Communication. I suspected I might encounter problems with the authorities if I did not possess the correct papers, particularly given my story: the effect on tourism of the April 2011 terrorist attack in Jemaa el Fna.

The Moroccan Tourism Board in London was fantastically supportive and helped expedite the paperwork. They also introduced me to the regional tourism office in Marrakech who promised an interview as well as a wingman to accompany me while I filmed.

As any tourist who has been to Jemaa el Fna knows as soon as you pull out a camera, one of the many buskers suddenly arrives with an upturned hat requesting money. So when I set up my tripod, camera and tangle of cables and microphones, I knew it was not going to be a straightforward session.

Fortunately the first day, Abdellatif the wingman had volunteered to accompany me and he spent a few hours by my side warding off mostly kids and occasionally musicians. Dressed in a black suit with dark sunglasses I think most people thought he was my bodyguard.

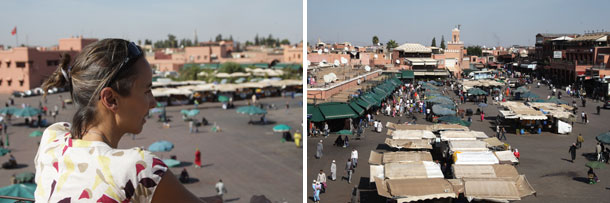

It was too noisy in the square to do a piece to camera -- although I should have tried, and wished I had -- and instead I did my stand-ups on a third-storey cafe balcony. Unfortunately I did not notice -- and nor did Abdellatif -- the foreign tourists behind me making faces and waving at the camera while I spoke about the impact of terrorism on tourism. It was frustrating to replay the footage that evening in my hotel room.

The following day the rain was torrential. “There are only 30 days of rain in Morocco every year,” a hotelier said to me which did not make me feel much better.

On my third and final day the rain was still coming down. I had planned only to film in the late afternoon/evenings when the square livens up but I sensed the weather would only deteriorate so I headed back to the square at dawn. I needed to secure some more footage, any footage, as well as some pieces to camera and in-vision headlines. Working solo was actually much easier than I imagined; it was cold and wet and most people seemed to feel more sorry for me than curious or offended. A few police hounded me but after I handed them a photocopy of my permit (in French) they moseyed off to finish their cigarettes.

It was the barbers of Jemaa el Fna who were my heroes of the day; they welcomed me into their shops, gave me shelter from the rain, poured me hot sweet mint tea and told me haunting tales about when the bomb went off a few doors down from their shops.

“Demain, reviens demain,” they said. “Demain, le soleil.”

I would not be back demain -- I had a plane to catch in an hour -- but I knew I would be back soon. Jemaa el Fna is swarming with life and surging with love, and will always be one of my favourite places in the world.