Newsweek - Only The Boldest

May 26, 2003

Stretching the idea of off-season travel to extreme new levels, they're defying the geopolitical elements in places like Syria, Zimbabwe and Bali.

Suzana Iorga has a secret vacation hideaway. It's called Syria. She and her husband, a French diplomat based in Cairo, fell in love with the country last summer on their first holiday trip there. Iorga, 30, raves about the spectacular Crac des Chevaliers Crusader castle and the desert oasis of Palmyra, one of the most fascinating archeological sites in the world, with evidence of human habitation dating back 75,000 years and some of the finest Roman ruins in existence. Even better, she says, they had the place practically all to themselves. "It was just great," she says. "There was almost no one. You have hectares of ruins. We saw no tour groups. In Palmyra, there were just three English tourists."

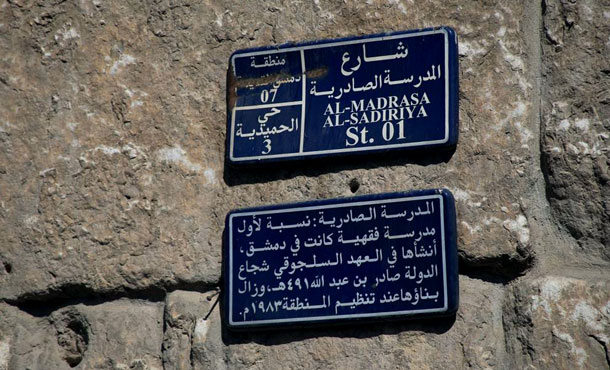

Iorga and her husband had stumbled onto one of tourism's great hidden treasures. In Syria, like just about everywhere else in the Middle East, jittery travelers have been scared off by war, civil unrest and threats of terrorism. Hardly anyone seems to notice that Syria has effectively escaped the recent turmoil (at least so far). Iorga and her husband are among the relatively few international travelers to savor the country's overlooked splendors. "We rented a car and just drove without any problem," she says. "The landscapes are great. There are no impediments to travel. Prices are very fair. The only thing that's inconvenient is that in many places you have no signs in English. If you want nice, quiet holidays, Syria is a good place."

These days the world has more than its share of deserted marvels like Syria just waiting for tourists to get over their worries and come back. War, instability and economic turmoil have created opportunities for the likes of Iorga and other venturesome travelers, who are stretching the concept of off-season travel to sometimes extreme new levels. They specialize in defying not only dubious weather but the uncertainties of the geopolitical climate. They're not backpacking kids, but they go where other educated, affluent professionals are reluctant to tread at the moment--places like Zimbabwe and Bali, for example. Their journeys have rewards that are vanishingly rare on the beaten track: extraordinary sights and experiences, enthusiastic service, solitude, tranquillity. And all at fire-sale prices.

One essential for this kind of tourism is a thick skin: friends are apt to say you're crazy. They may be right. They've seen the grim headlines and the dire travel advisories. Still, they haven't necessarily looked at a map. The Middle East is a big place, contrary to what some people apparently think. "My friends were surprised and nervous when I said I was going to Beirut," says British Internet entrepreneur Azeem Azhar, who vacationed in Lebanon during the showdown in Iraq. "But the reality is you are a thousand miles from Baghdad. --Being scared there is like being worried in London about a dockworkers' strike in Gdansk." Even so, it takes a long time to live down the kind of reputation Beirut earned during the 1980s as a nest of terrorists. And the Mideast's problems never end. Take Egypt, where just as the travel industry was recovering from the tourist massacres of 1997, the market was devastated again by the horrors of 9-11.

Serious risk lovers can visit Zimbabwe. Robert Mugabe's country used to be regarded as a model for African economic management, as well as one of the continent's safest and most stunning safari destinations. For the past three years, though, Mugabe's desperate efforts to keep power have skidded the country into chaos, hunger and near civil war. Those problems didn't stop New York artist Peter Sabbeth and his wife, Melissa Green, from spending their honeymoon at Lake Kariba two years ago. Others might object to taking a pleasure trip in such a place, for fear of exploiting its misery or encouraging an abusive regime. All the same, Sabbeth is convinced he did the right thing by helping to support the local economy. "Everyone was staying away," he says. "I felt we would be doing the most good by going there--and also have the best time. I'd still go now, and I'd recommend it to anyone."

Not that it's paradise. Lines at filling stations can sometimes last four days--and that's a mere nuisance by Zimbabwean standards. As the collapse of Zimbabwe's tourism industry has compounded its economic crisis, street crime has worsened. A 27-year-old Australian tourist was stabbed to death at Victoria Falls in January. Outside the cities, travelers are advised to avoid driving at night, when armed thugs like to set up roadblocks and collect "tolls."

At the same time, it's best to steer clear of Mugabe's security forces; they frequently detain travelers on flimsy charges, suspecting them of being spies or foreign journalists. Security forces at a checkpoint recently shot a foreigner who was not carrying the proper identity papers. And it's also best to save your camera for the wildlife. Photographing some official buildings (the president's house, for example) is a crime punishable by two years in prison. Two Canadians were detained in February because one, a commercial photographer, was spotted photographing a billboard.

If that's too adventurous, how about the beaches of Bali instead? The island has been quiet since October, when a terrorist bombing killed more than 200 Western nightclubbers. It's far too quiet for many Balinese, half of whom depend on tourism for their livelihoods. Travel is down 70 percent, and five-star suites are still available for the upcoming high season. A week for two at a top-rated hotel can now cost as little as $230, including meals, transfers, tours and spa treatments. "Extremist elements may be planning additional attacks targeting U.S. interests in Indonesia," warns the U.S. State Department's Web site. Yet islanders insist there's no hint of any hostility to foreigners, nor any indication that another attack is likely.

Ray Gajardo says he's going there this summer. A resident of southeast England, the semiretired musician says his 30-year-old son Marc called home from Bali early last October, utterly enraptured with the place. Marc made his parents promise they would visit the island someday.

A week later their son became the first British fatality to be identified among the bombing's victims. "As far as I'm concerned, Bali is the safest place on the planet right now," says Ray. "I mean, lightning doesn't strike the same place twice."

That's only a myth, of course. Still, people need to make up their own minds about what's safe. Voyagers can get a rough sense from sources like the U.S. State Department's travel advisories on the Web (state.gov/travel). And local travel experts often give more nuanced advice on avoiding dangerous areas within a country. Hilary Bradt, founder of the U.K.-based Bradt Travel Guides, has practically made a career of risk assessment. It's an art, whether in Bali or on your home street. "I wouldn't go to Algeria, because tourists have been deliberately targeted for killings and kidnappings there," Bradt says. "But I wouldn't have hesitated to travel to Iraq in, say, October. I know how culturally hospitable the people are there."

The most intrepid travelers seem to be more afraid of disease than of violence. Even then, there are exceptions. Adam Whitford, 31, an Australian who directs an outdoor advertising firm, just got back from Hong Kong--SARS city. "It costs 40 percent less to stay there now," Whitford explained. "I think this whole thing is overkill." When we last spoke to him, he was feeling fine.