Vanity Fair - Beside the sacred waters

November 2017

Among cypress forests and holy rivers, Michelle Jana Chan discovers change and continuity in the traditions of the Shima peninsula.

I love the odd, the outlandish and the outrageous sides of Japan, from cuddling a hedgehog at Harry’s Hedgehog Café to standing on the pedestrian bridge in Tokyo’s Harajuku district to watch the fashion show — of cosplayers, anime otaku, Decora girls, rockabilly dancers, roller skaters, Visual Kei fans and Lolitas. I have a penchant for robots, too, which sometimes here substitute for sales assistants, and genuinely seem to engage with eye contact and a shake of the hand. And then there’s the extreme sanitation. The shiny bubbly rubbish trucks look like they rolled out of a Hello Kitty cartoon, and on this latest trip I saw a man vacuum-cleaning the pavement outside Tokyo’s Apple Store.

As much as I adore Japan’s wacky capital, I also stand in wonder at the heritage of the Imperial city of Kyoto with its extraordinary array of temples and shrines. One of my favourite days is to stroll along The Philosopher’s Path, a flagstone trail under cherry trees running beside a stream where I spot carp in the shallow waters, and pop into temples to partake in rituals that forecast future or destitution, before breaking off to wander the higgledy-piggledy neighbourhoods between Ginkakuji and Nanzenji.

Yet what I love most about Japan is the spaces in between: not the big cities but the provinces, which showcase the ordinary and everyday rather than glimpses of our future or the past. One of my favourite diversions is the Shima peninsula between Tokyo and Kyoto, which represents a perfect midway pause. This region offers an insight into Japan’s remarkable cuisine and its indigenous religion, Shinto, backdropped by some staggering scenery. It is a rugged coastline of coves, natural harbours, inlets and islands on the fringe of the Pacific Ocean. From the cliffside town of Toba, the peninsula sweeps around to Ago Bay dotted with a flotilla of oyster rafts used in pearl cultivation. Locals come here to go to the beaches for surfing, for stand-up paddle-boarding and sea-kayaking. The views are big; from atop Daiosaki Lighthouse one can see the curvature of the Earth, a sweeping deep-blue panorama.

But the main reason the Japanese have come here for centuries is because it is home to a revered pilgrimage site, the inscrutable Ise-Jingu Shrine which lies at the heart of Shinto. Built beside the Isuzu River, it is dedicated to the religion’s most important deity, Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess.

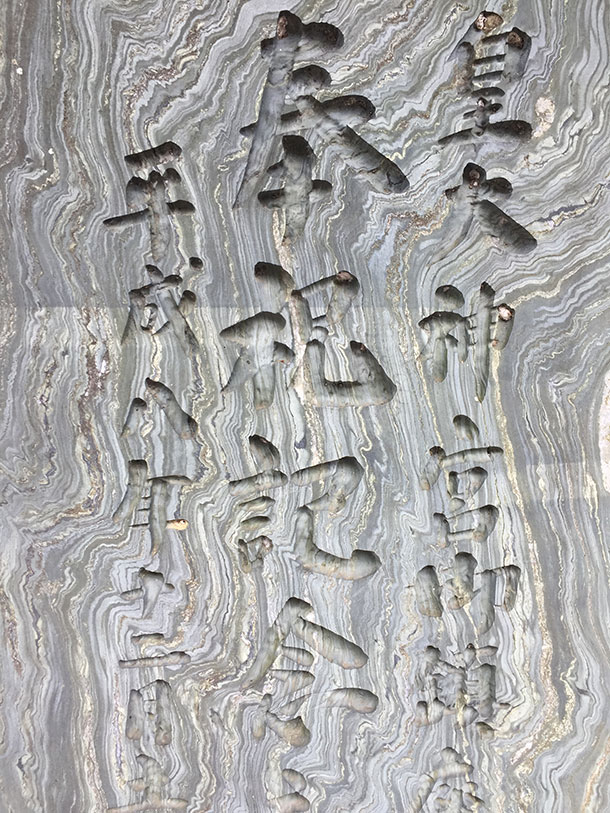

Starting at the 100-metre-long Uji bridge, I pass under two large torii gates, one at each end, which serve as a portal from the world of the profane to the sacred. I wander the lattice of gravel trails under the dappled shade of ancient cedar trees and pine, stopping to perform the ritual of washing my hands and rinsing my mouth with cool river water.

The shrine itself is refreshingly underwhelming. Visitors cannot enter the inner courtyard but only peer over a fence at the corner of the elusive structure, which is itself said to house a sacred mirror used to lure Amaterasu out of a cave in order to bring light to the world. The restricted view makes it all the more mysterious.

But the most intriguing aspect of the shrine is how very contemporary it is, rather than its museum state, because — astonishingly — every 20 years the structure is demolished down to its foundations, before being rebuilt a stone’s throw away. This cycle has been repeated for more than 1,300 years, celebrating the idea of renewal, the impermanence of material things, as well as ensuring that the skills and techniques of the craftsmen are never lost, from the precise joinery to the exquisite stonemasonry. For example, not only the eaves, but the entire roof structure is set using joints that slowly settle; the gap closes over a period of about 20 years, miraculously aligning just when it is time again to tear down the building. Genius. Almost unbelievably, in 2033 the 63rd reconstruction is slated to take place.

To explore this region I make my base at Amanemu, which itself may have employed some of these brilliant craftsmen to build the hotel. Located on the Kii Peninsula and designed by Aman favourite Kerry Hill, there are 24 suites and four two-bedroom villas with low-slung slate roofs and cedar exteriors. Inside there are echoes of a traditional ryokan with the use of Japanese Hinoki cypress wood, sliding shoji paper walls and a private granite onsen, or mineral hot spring bath.

I headed along the coastal road to Shima to meet a man with a royal stamp of approval. I could smell the place before I stumbled upon it: a swirl of ash and the fumes of pungent fermenting tuna. When I walked through the open entrance into the dark smokehouse, my eyes took a while to adjust. Yukiaki Tempaku peered out through the searing haze and bowed deeply, welcoming me into his atelier, for what he does here is surely an art form.

Maruten is a fourth-generation enterprise housed in a building that dates back even further. “But I’m still a baby chick,” the 58-year-old told me grinning, and with a nod to his ancestors. “I am still learning.”

He sat me down on a stool with a cup of green tea and handed me a stuffed toy of a segmented fish held together with Velcro. He then started pulling it apart to show me the different cuts of a bonito, or a young skipjack tuna. This is the fish he dries, ferments and smokes with burning oak until it becomes katsuobushi, as it is known here. After the six-month process it has become one of the hardest foods in the world with the texture and look of antique teak. “Warriors used to carry a sword on one side of their bodies, and a fillet of smoked bonito on the other,” Tempaku tells me. “They were of equal importance.”

At one time it was served at the Imperial court and it is also one of the formal offerings at the Ise Jingu Shrine, an honour held in even higher esteem (the priests have not missed a day in 1,500 years). It is now Tempaku who supplies the shrine with a contribution of bonito twice a day. He offers me a bowl of consommé made from the concentrate of katsuobushi; it tastes fresh and unadulterated, more akin to the virginity of coconut water than something oily and marine. This is the soup stock — called dashi — that forms the base of almost all Japanese cuisine.

“When it comes to culture and cuisine, Tokyo looks to Kyoto,” Tempaku tells me. “And Kyoto? It looks to Ise-Shima.”

The region also flaunts some of the country’s finest rice, salt and sake, but it is the seafood here which is truly exceptional and, as I discovered, it is best eaten cooked over hot coals in a corrugated iron shack on a cliff edge. That’s where I found myself with two of the region’s ama, the “women of the sea” who freedive for spiny lobster, sea urchins and abalone.

Michio Nakamura, 65, and Terumi Uemera, 61, served me up a platter, which also included seaweed, grilled mackerel, scallops, turban shells, clams, octopus and oysters — and explained to me the way they forage in the shallows offshore, or out at sea, armed with a rope and weights descending to depths of up to 20 metres. When their breath runs out, they tug the rope to be pulled swiftly up to the surface, usually by their husbands. They use flat blades to slice abalone off rock, and hooks to grab at sea urchin.

There are about 2,000 ama remaining in Japan and nearly half of them come from this region. But the practice, which dates back at least a thousand years, is on the decline. The pair tell me there is one 33-year-old in training, but nearly all of the women are now over 50 and the eldest is 80.

Both Nakamura and Uemera have been diving for over half their lives. Nakamura remembers when she was only a novice 40 years ago, how her mother-in-law stood by to study her catches; when she came home empty-handed, she felt a deep sense of shame. Freediving can be a risky business, too, and she’s had some close calls, mostly after becoming tangled in stray fishing nets. A few hundred metres away from where we eat is a shrine on a jetty dedicated to divers who never returned to the surface. Nakamura and Uemera both wear bonnets embroidered with a cross-hatch grid believed to give them protection, and a star drawn with one stroke to represent the hope that you always come home.

“It’s women’s work,” Nakamura tells me, when I ask her why men don’t freedive here. “We can get some housework done, do an hour or so of diving, before coming home to cook lunch.” She makes it sound as pedestrian as getting a mani-pedi. Others say the reason women took up the role is because they have more body fat to protect them against the icy chill of the northern Pacific.

I watched some of their colleagues in action offshore. The leapt out of a boat and duck-dived down, the pale soles of their feet disappearing into the inky depths. A couple of minutes later they calmly surfaced, carefully dropping their catches into floating wooden tubs that also serve as buoys, then opened their mouths slightly and exhaled slowly, making a high-pitched whistling sound known as isobue. It sounds like the Sirens in Greek mythology, who lured sailors on to rocks with their captivating voices.

The women who continue to dive want to preserve the tradition but also understand its clash with modern life; neither Nakamura and Uemera are pressuring their own daughters into joining the trade.

“The ama will continue in some form,” Nakamura says. “It might be different in the future but it has already changed. Nowadays we wear wetsuits and goggles. Our grandmothers didn’t do that.”

Back at the smokehouse, Tempaku brings out a lathe and grates some katsuobashi, the same way one might work a piece of wood. The shavings are a pretty translucent pink. He sprinkles them over a bowl of steaming soft wet rice. It doesn’t taste of fish, just a hint of the ocean. Perhaps it really is the food of the Gods.

Before I leave, Tempaku hands me the gift of a vacuum-packed parcel of smoked bonito with dried tomato, a modern twist on his traditional fare; the graphic packaging is bold and contemporary, yet done by a 13th-generation woodblock master from Kyoto. There seems to be a strong awareness here of the need to move on in order to survive. Maybe it is this tradition of regeneration that is Japan’s secret to success — whether adapting ancient rituals, donning a pair of goggles, or replacing a building with an exact copy over and over again.